Irving Penn has passed away. He had a knack for turning Chanel’s adage — elegance is refusal — into a style that might be called, paradoxically, lushly minimal. With the fewest possible elements, he could coax out the drama of interior life.

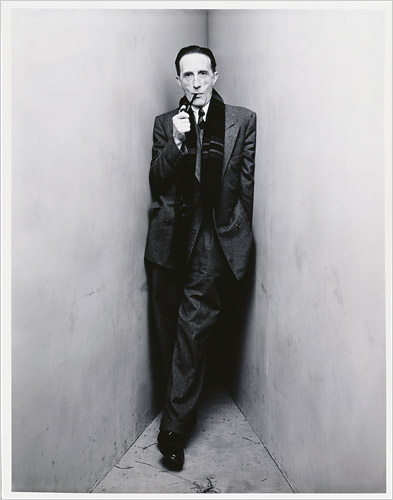

His early work was marked by a curious backdrop. He stuffed his subjects, many of them art-world royalty, into a tight corner. The claustrophobic setting enabled Penn to assert a kind of cruel power that, by showing how people responded to their surroundings, told us about their demeanors. In his words: “This confinement, surprisingly, seemed to comfort people, soothing them. The walls were a surface to lean on or push against.” As an exception, you have Georgia O’Keefe, slanting subtly, who felt so reduced by the converging walls that she demanded her photo be destroyed. As confirmation, you have Marcel Duchamp, a dapper picture of composure and self-possession, whose puffing pipe signaled that he relished the enclosure.

Marcel Duchamp, New York, 1948

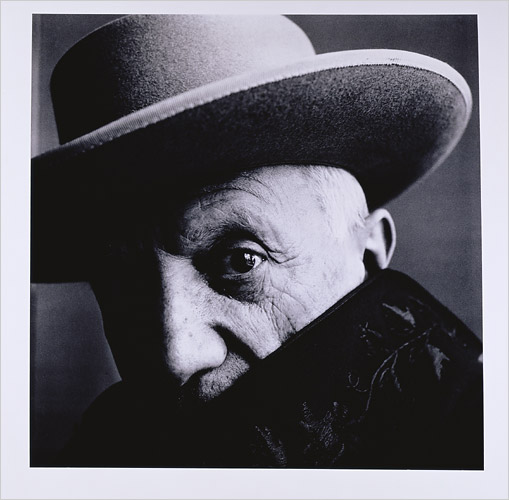

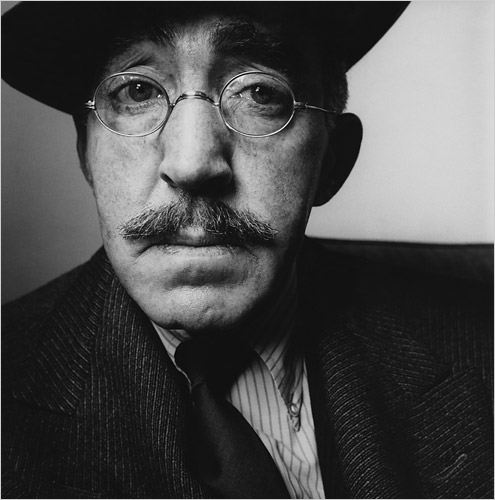

Gradually he shifted from his corners to a cloudily anonymous backdrop, a sooty swath of medium gray that threw his subjects forward toward the viewer. This was his signature style in the 1950s. Moving his camera much closer, he exalted the face and eyes as matrices of expression. Often casting a sideways light on his sitters, he hinted at the complexity that lay behind the face, orchestrating a clash of light and shadow that reflected some inner twoness. They also read as a truce between revelation and mystery. John Szarkowski compared two famous images:

Penn’s famous portrait of Picasso, with the great cyclopean eye, the bullfighter’s cape, the ethnic hat, the dramatic lighting, etc., seems to this viewer a marvelous triumph of skill, an admirable act of legerdemain, but something less than a true portrait, if one takes as a standard the picture of S. J. Perelman, for example. This is the record of a collaborative disclosure, or discovery, of a self.

Pablo Picasso, Cannes, France, 1957

S.J. Perelman, New York,1962

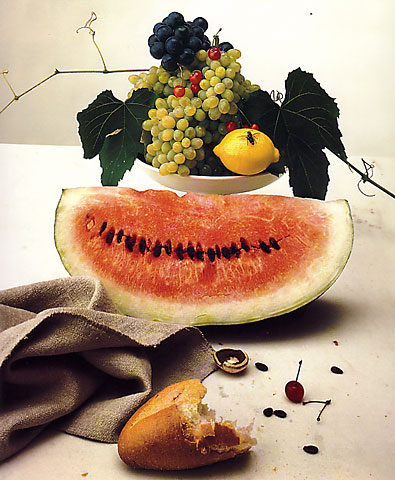

In the end, many of my favorite Penn photographs weren’t portraits at all. His images of cigarettes stood out to me as alchemical: lead into gold. Szarkowski had a theory about them: “The lipstick on the dead cigarette butt, the beetles, flies, stains, mice, raveled carpets and moldering walls that recur with such frequency in Penn’s work might be explained as a quiet dissent from the general model of perfect elegance that prevailed at Vogue during Penn’s early years there.” His still lives attempted something else. They gave form to his painterly ambitions by not relying on the camera alone, but on principles of art. They sought to arrest time’s movement, to preserve life’s color from decay simply by lending living things, through surprising placements and pairings, the soft touch of eternity.

Still Life with Watermelon, New York, c. 1947

1 Trackback