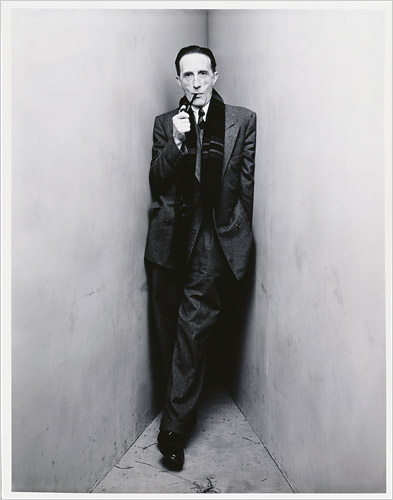

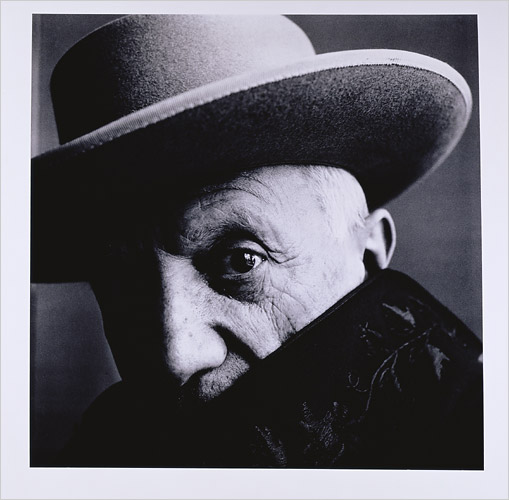

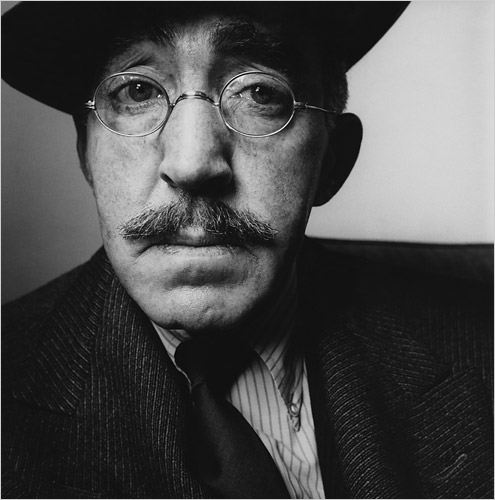

Sleigh Bells have drawn heaps of critical attention in no time flat. What could be the appeal? That, as they told an old colleague of mine, everything is glossy but something is off? I think you can trace it to the collision of sensibilities between Derek Miller, a guitarist from a Florida post-hardcore band, and Alexis Krauss, who’s worked as a schoolteacher, wedding singer, session vocalist, and teen member of a girl group. Miller offers varieties of primitivism: homemade beats plus squeals and squalls of roughly guitarlike noises. Krauss, on the other hand, boasts a diversity of talents that reflects her diversity of experience. This goes for both her voice—an instrument that can switch gears on a dime—and her body—an instrument that, in the fiery tradition of Joan Jett and Karen O, fastens into an ecstatic state that feels at once confronting and inviting. Stirring together ferocity and feminine innocence, this 24-year-old whirlwind of sound and motion launches out bratty roars and lusty moans, graceful hand gestures and dizzying hair whips, keeping stillness and silence at bay, the not-so-calm core within Miller’s maelstrom of brute riffs and booms.

Some are bothered by Sleigh Bells’ use of an iPod in their live show. I wonder if these people are troubled by Beach House’s prerecorded drum tracks. Frankly, I don’t see the issue. A live act need not conform to some eternal template of rock-band roles. Here we can zero in on the two true sources of action. Or in the case of “Ring Ring,” above, one live center plus one warmly looped center.

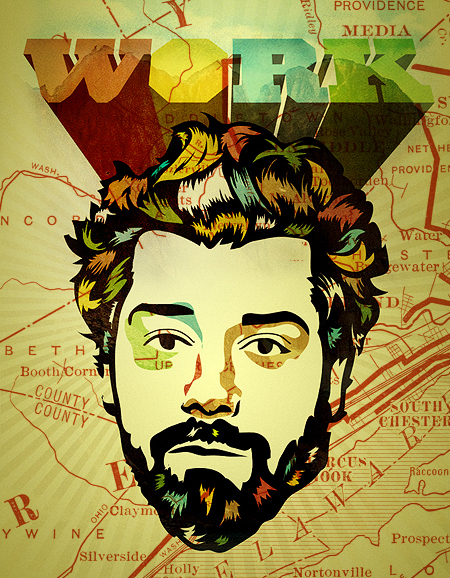

Photo credits: Will Deitz, Pitchfork; James Ryang, NYT.